Josslyn Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll

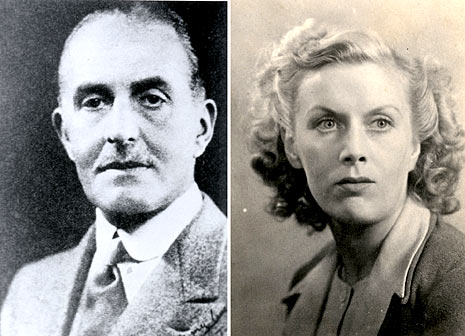

Josslyn Victor Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll (11 May 1901, Mayfair, London – 24 January 1941, Nairobi-Ngong road, Kenya) was a British peer, famed for the unsolved case surrounding his murder and the sensation it caused during wartime Britain.

Early life

Hay was the eldest son of the diplomat Victor Hay, Lord Kilmarnock (later Earl of Erroll) and his wife Lucy, the only daughter of Sir Allan Mackenzie, 2nd Baronet. In 1911, he attended the coronation of George V and carried his grandfather’s coronet. He began at Eton College in 1914 but was dismissed two years later.

Although possessing one of Scotland’s most distinguished titles, the earls, by this time, had no wealth, and had to develop careers to earn their living. In 1920, Hay was appointed honorary attaché at Berlin under his father, who was earlier appointed chargé d’affaires there before the arrival of Edgar Vincent, 1st Viscount D’Abernon. His father was soon appointed High Commissioner to the Rhineland, but Hay stayed in Berlin and served under Lord D’Abernon until 1922.

After passing the Foreign Office examinations, Hay was expected to follow his father into diplomacy, but instead became infatuated with Lady Idina Sackville, a daughter of Gilbert Sackville, 8th Earl De La Warr, divorced wife of the politician Euan Wallace and the wife of Charles Gordon. Lady Idina soon divorced her husband in 1923 and she and Hay were married on 22 September 1923.

Kenya

After causing a society scandal due to their marriage – she was twice-divorced, notoriously unconventional in many ways, and eight years his senior – Hay and his wife moved to Kenya in 1924, financing the move with Idina’s money. Their home was a bungalow on the slopes of theAberdare Range which they called Slains, after the former Hay family seat of Slains Castle which was sold by Hay’s grandfather, the 20th Earl, in 1916. The bungalow was sited alongside the high altitude farms which other white settlers were establishing at the time.

The Happy Valley set were a group of elite, colonial expatriates who became notorious for drug use, drinking, adultery and promiscuity amongst other things. Hay soon became a part of this group and accumulated debts. After Hay had inherited his father’s titles in 1928, his wife divorced him in 1930 because he was cheating her financially and Hay married the divorced Edith Maud Ramsay-Hill on 8 February 1930. They lived in Oserian, a Moroccan-style house on the shores of Lake Naivasha and his new wife succumbed to the hedonistic lifestyle of Happy Valley.

On a visit to England in 1934, Lord Erroll joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and on his return to Kenya a year later, became president of the Convention of Associations. He attended the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1936 and was elected to the legislative council as member for Kiambu in 1939. On the outbreak of World War II that year, Lord Erroll became a captain in the Kenya Regiment and accepted the post of Military Secretary for East Africa in 1940.

On 13 October 1939, Lady Erroll died. At the Muthaiga Country Club in 1940, Lord Erroll met Lady Diana Broughton, the wife of Sir Jock Delves Broughton, Bt. (and, ultimately, Baroness Delamere).

Murder

Delves Broughton learned of the affair and after spending a night with Lady Delves Broughton, Lord Erroll was found shot dead in his Buick at a crossroads on the Nairobi-Ngong road on 24 January 1941. Sir Jock was accused of the murder, arrested on 10 March and stood trial from 26 May. There were no eyewitnesses to the killing; the evidence against him proffered in court was weak; and his hairdresser was also foreman of the jury. Because of these factors, Sir Jock was acquitted on 1 July. He committed suicide in England a year later.

Lord Erroll was buried in the graveyard of St Paul’s Church, Kiambu, Kenya next to his second wife. His earldom and lordship of Hay passed to his only daughter,Diana,by his first wife, whilst his barony of Kilmarnock passed to his brother,Gilbert

Compelling evidence from beyond the grave has enabled the final piece of the jigsaw in Kenya’s Happy Valley killing to be fitted into place. Judith Woods reports From The Daily Telegraph 11th May 2007

It was the unsolved high society murder that fascinated the nation for more than half a century. With the decadent backdrop of the infamous Happy Valley set in Kenya, the killing of Josslyn Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll, in 1941 was as intriguing as it was shocking.

Was it a crime passionnel as a result of Erroll’s notorious womanising or a political execution carried out because of his Right-wing connections? Who pulled the trigger on the gun – and where did the assassin hide the weapon, which has never been found? For 66 years the gripping, glamorous scandal, which was later immortalised in the book and film White Mischief, starring Charles Dance and Greta Scacchi, has shown no signs of being solved.

Now, definitive new evidence has come to light, finally revealing who shot Erroll and how this most premeditated of crimes was committed. Extraordinary tapes from beyond the grave, together with fresh witness accounts, have solved the mystery that has baffled historians and investigative authors for decades.

Back in 1941, Sir “Jock” Delves Broughton was put on trial for the murder of Erroll, who was his wife Diana’s lover. Although sensationally acquitted, months later Delves Broughton committed suicide, fuelling further heated speculation.

And now, in a fateful echo of the past, the very week that Delves Broughton’s granddaughter, the brilliant yet troubled fashion stylistIsabella Blow, apparently took her own life by poison at her Cotswolds home, The Daily Telegraph can disclose that it was indeed her grandfather who murdered the Earl of Erroll.

The woman behind these new revelations is Christine Nicholls, the author of Red Strangers: The White Tribe of Kenya, a history of white colonisation in the country.

“I have spent years puzzling over the murder,” says Nicholls. “I was always certain that Delves Broughton had done it, but up until now, there was no proof. At last we know what happened the night Erroll was shot – and the details are utterly compelling.”

Nicholls was given tape recordings and witness statements by a fellow author, Mary Edwards, wife of the former deputy high commissioner in Kenya, who wrote a book about the country that was never published. Last year, shortly before her death, she handed her material to Nicholls. Some of the interviews date back to 1987, because the key witness on the tape had asked for the contents to be kept secret until some years after his death, which occurred in 1991.

“It’s a hugely exciting discovery,” says Nicholls. “Some commentators suggested that it was Diana who shot her lover when he tried to end the relationship; others that Erroll was murdered by one of his other jealous lovers, or a cuckolded husband who couldn’t bear the shame.

“There have even been claims that Erroll’s death was due to a secret service conspiracy, and that he was executed because he was suspected of collaborating with the Germans in wartime and belonged to a renegade group including the Duke of Windsor and Rudolf Hess. People have always been enthralled by this mystery.”

This was certainly the case at the time. Even at the height of the Second World War, the trial transfixed Britain and marked the beginning of the end for Kenya’s hedonistic colonial elite. But to comprehend the crime, one must understand the louche, amoral world of Happy Valley, that enclave of hedonism in the White Highlands of Kenya, notorious since the Twenties as an aristocratic playground.

As World War II raged in Europe and beyond, and Africa suffered its familiar tribulations of locusts, disease and droughts alternating with floods, the fast-living upper classes carried on as though nothing had changed from their pre-war hey-day. They drank to excess, took cocaine, abused their servants and slept with each other’s wives: the only sin was being a bore.

Josslyn Victor Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll and Hereditary High Constable of Scotland, was a serial womaniser and inveterate gambler, who specialised in seducing rich married women. Himself twice-married (his second wife died of heroin addiction), the predatory Erroll was loathed and feared by husbands, but his status was assured when, at the start of the war, he was appointed assistant military secretary for Kenya, despite a previous link with the Fascists.

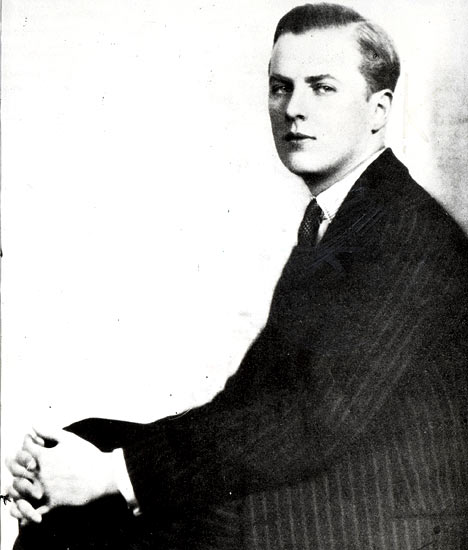

Then, in November 1940, a new couple arrived in the colony. Sir “Jock” Delves Broughton, 11th baronet and formerly patron of both Doddington Park in Cheshire and Broughton Hall in Staffordshire, was accompanied by his new wife, Diana.

Delves Broughton was 56, and the effects of a thrombosis caused him to drag his left foot. Diana was an alluring divorcée, with deep blue eyes and elegant, arched eyebrows. Aged 26, she was well aware of her powers of attraction.

Even en route to Kenya, Diana had embarked on an affair with a fellow passenger, and ignored her husband, who was too smitten to object. Not long after they arrived in Nairobi, Diana met Erroll, who was by now sporting the khaki tropical uniform of a captain in the East African forces, and, despite the fact that he already had a mistress, soon became his lover.

Their passion was shortlived. Three months later, on the night of January 24 1941, Erroll was found shot dead in his car. Shockwaves reverberated through this privileged community at the thought of a killer in their midst.

Prior to the murder, Delves Broughton appeared to have been sanguine about his wife’s philandering, although given that promiscuity was de rigueur in Happy Valley, it would have been considered bad form to have behaved otherwise.

It struck no one as strange, then, that on the night of Erroll’s death, Delves Broughton, Diana, Erroll and a friend, June Carberry, all dined together at the Muthaiga Club outside Nairobi. When Diana and Erroll headed off to go dancing, Delves Broughton merely told Erroll to bring his wife back by 3 am.

Erroll and Diana returned at 2.30am. He went into the house to bid her goodnight, then returned to his Buick and drove off. Half an hour later, his body was found slumped in his car several miles away by a milkman. He had been shot through the temple and there were powder burns at the side of his face. On the back seat of the car there were unexplained white scuff marks.

Delves Broughton was the obvious suspect and was brought to trial for the murder. The media coverage threw into sharp relief the extravagant lifestyles and depraved social mores of the idle rich in Africa, who revelled in cocktails and casual sex while Britain suffered the deprivations of wartime rationing and nightly raids by German bombers.

Delves Broughton was acquitted in what was widely regarded as a blatant miscarriage of justice, but there was no proof to convict him. He was never accepted back into what remained of the Happy Valley fold, however. Diana had by now taken up with another wealthy lover, whom she went on to marry. Subsequently she married for a fourth time, and became Lady Delamere.

She stayed on in Kenya while the disgraced Delves Broughton sailed home. Several days after arriving back in England he committed suicide in a bedroom at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool, by injecting a lethal overdose of morphine.

No one has ever known for sure whether he killed Erroll. At his trial, his defence argued that he couldn’t have committed the murder because the bullet had clearly been shot from either inside the car or from the running-board. This meant he wouldn’t have had any way of returning to his house other than on foot.

Erroll had been killed some time after 2.30 am. Yet at 3.30 am Delves Broughton had knocked on June Carberry’s door to check she was all right as she was known to be a heavy drinker. The scene of the crime was 2.4 miles by road from his house, or one mile through the bush, distances that, given his limp, Delves Broughton could never have covered in that time.

But according to the new evidence, Delves Broughton, who was wearing a pair of white plimsolls, had slipped into the back of Erroll’s car while Erroll was seeing Diana safely indoors after they’d been dancing. When Erroll drove off and turned on to the main road back to Nairobi, Delves Broughton shot him. Then he was picked up further along the road at a pre-arranged spot by another car, which drove him home.

“The tape recording I have gives the name of the driver who collected Delves Broughton,” says Christina Nicholls. “The driver was Dr Athan Philip, an ear, nose, throat and eye specialist who was a refugee from Sofia in Bulgaria. He was a neighbour of Delves Broughton and his practice wasn’t going very well, so he was happy to take a generous payment for doing a pick-up.

Whether he knew exactly why he had to be at a certain place at a certain time isn’t clear, but the reason Delves Broughton had told Erroll to bring Diana home by 3 am was so that he could put his plan into action.” The tape itself is a recording by Dan Trench, whose parents were farming partners with June Carberry’s family. Carberry told the Trenches, including Dan, how the murder was committed, but they never spoke to the police.

“Dan Trench didn’t feel he could repeat the story until he was old and frail in 1987,” says Nicholls. “Even then, having made the tape he didn’t want it to become public until well after his death.”

Nicholls has also pieced together further crucial parts of the jigsaw. Juanita, the 15-year-old daughter of June Carberry’s husband from a previous marriage, visited the Delves Broughton house on the day of the murder. The atmosphere was

tense and Diana cried uncontrollably.

“A servant came in to say there was a fire in the garden on the manure heap. Juanita saw clothes burning and a pair of good white plimsolls smouldering on top,” says Nicholls. “Shocked at the waste, Juanita suggested they be given to an African servant, but Delves Broughton dismissed the idea. It was the white rubber soles of the plimsolls that had made the mysterious marks inside the car.”

Nicholls has spoken extensively to Juanita, who is now in her eighties and lives in a flat in Chelsea. She has said that, two days later, Delves Broughton told her not to be surprised if the police turned up to arrest him for the murder of Erroll.

“Juanita was very taken aback and said: ‘Oh no, you couldn’t have’,” says Nicholls. “Delves Broughton’s response was deadpan. ‘But I did, and I have just dropped the gun over the bridge into the river at Thika’.”

The gun didn’t stay there for long. Delves Broughton also confessed to June Carberry that he was the murderer and told her where he had disposed of the weapon. June felt there was a risk he might have been seen throwing the gun into the shallow water, and sent a servant to dive into the river to retrieve it.

“The gun was taken to Eden Roc, the hotel owned by the Carberrys in Mailindi on the coast, and concealed in the roof of the workshop,” says Nicholls. “Later, the hotel maintenance engineer unearthed the weapon in a routine check and took it to the Carberrys.”

Among the correspondence given to Nicholls were emails sent by the maintenance engineer’s cousin, who told her the story of what had occurred.

“He said that when the gun was brought to him, John Carberry went white as a sheet, jumped in his car and took off to Malindi town. There he borrowed a big deep-sea fishing boat, headed out at top speed over the reef and dropped the gun into deep water, where it remains to this day.”

It is a potent image of a terrible secret buried forever. But, 66 years later, the truth has finally come to light, conjuring up yet again the ghosts of Happy Valley and the bitter passions that drove one member of the British nobility to slay another in cold blood. Yet, despite solving the puzzle at the heart of this hitherto enigmatic crime, Nicholls feels the fascination surrounding such a singular murder will live on.

“People love a good mystery,” she says. “It’s such an intriguing case that I suspect that speculation about the details will continue for years to come.”

From The Daily Mail 2007:

White Mischief’ murder finally solved after 66 years

Last updated at 17:32 11 May 2007

It had all the makings of a gripping, glamorous murder mystery.

A British aristocrat is shot dead amid the lap of luxury in colonial Kenya.

The killing of Josslyn Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll, in 1941 gripped a nation caught up in the grind of war.

Immortalised in the book and film White Mischief, starring Charles Dance and Greta Scacchi, the unsolved case was for decades no closer to being solved

For 66 years, theories have ranged from a crime of passion brought about by the earl’s notorious womanising to a political assassination based on his right-wing connections.

Why has the gun never been found? Who was the assassin?

But now the mystery has been solved after dramatic new evidence came to light.

Months after the murder, Sir ‘Jock’ Delves Broughton stood trial for the murder of Erroll.

The dead man had been sleeping with his wife Diana – so there was a clear motive.

Despite his sensational acquittal, his suicide soon after fuelled further heated speculation.

In an eerie echo of the past, this week Delves Broughton’s granddaughter, the brilliant fashion stylist Isabella Blow, apparently took her own life at her Cotswolds home.

Now amazing new tapes and witness accounts have finally solved the mystery that has baffled detectives for decades.

The author of a new book on East Africa, Elspeth Huxley’s A Biography by Christine Nicholls was given the crucial evidence by a fellow writer shortly before her death.

“It’s a hugely exciting discovery,” says Nicholls. “Some commentators suggested that it was Diana who shot her lover when he tried to end the relationship; others that Erroll was murdered by one of his other jealous lovers, or a cuckolded husband who couldn’t bear the shame.

“There have even been claims that Erroll’s death was due to a secret service conspiracy, and that he was executed because he was suspected of collaborating with the Germans in wartime and belonged to a renegade group including the Duke of Windsor and Rudolf Hess. People have always been enthralled by this mystery.”

Even at the height of the Second World War, the trial transfixed Britain and marked the beginning of the end for Kenya’s hedonistic colonial elite.

As Europe and other parts of the world endured World War II, the fast-living upper classes carried on as though nothing had changed from their pre-war hey-day. They drank to excess, took cocaine, abused their servants and slept with each other’s wives.

Josslyn Victor Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll and Hereditary High Constable of Scotland, was a serial womaniser and gambler, who specialised in seducing rich married women.

Twice-married (his second wife died of heroin addiction), the predatory Erroll was feared by husbands, but at the start of the war he was appointed assistant military secretary for Kenya, despite a previous link with the Fascists.

His fate was sealed when in 1940 a new English couple arrived in the colony. Sir ‘Jock’ Delves Broughton, 56, and suffering from thrombosis, was accompanied by his new wife, Diana. Thirty years his junior with deep blue eyes and elegant, arched eyebrows, she was well aware of her powers of attraction. Diana had embarked on an affair with a fellow passenger even on their way to Nairobi. Her husband was too smitten to object. Soon after there arrival, Diana met Erroll and, despite the fact that he already had a mistress, soon became his lover. But their passion was shortlived. On the night of January 24 1941, Erroll was found shot dead in his car. Delves Broughton had appeared sanguine about the affair, and on the evening of the murder, Erroll had dined with Diana and his husband before he took his lover dancing. Half an hour later after dropping her off, he was shot in his Buick. Unexplained white scuff marks were found on the back seat. As the obvious suspect, Delves Broughton was brought to trial for the murder. The media coverage threw into sharp relief the extravagant lifestyles and social mores of the idle rich in Africa while Britain suffered wartime rationing and nightly raids by German bombers. In what was considered a blatant miscarriage of justice Delves Broughton was found not guilty, but there was no proof to convict him. Diana stayed on in Kenya while the disgraced Delves Broughton sailed home. Several days after arriving back in England he committed suicide in a bedroom at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool, by injecting a lethal overdose of morphine.

The new evidence explains exactly how he carried out the murder. Delves Broughton, who was wearing a pair of white plimsolls, had slipped into the back of Erroll’s car while Erroll was saying goodbye to Diana. As Erroll drove off, Delves Broughton shot him. The killer was then picked up further along the road at a pre-arranged spot by another car, which drove him home.

“The tape recording I have gives the name of the driver who collected Delves Broughton,” says Christina Nicholls.

“The driver was Dr Athan Philip, an ear, nose, throat and eye specialist who was a refugee from Sofia in Bulgaria. He was a neighbour of Delves Broughton and his practice wasn’t going very well, so he was happy to take a generous payment for doing a pick-up.

“Whether he knew exactly why he had to be at a certain place at a certain time isn’t clear, but the reason Delves Broughton had told Erroll to bring Diana home by 3 am was so that he could put his plan into action.”

The tape was made by Dan Trench, who parents were farming partners with the family of a friend of Erroll, Diana and Delves Broughton.

Carberry told the Trenches, including Dan, how the murder was committed, but they never spoke to the police.

“Dan Trench didn’t feel he could repeat the story until he was old and frail in 1987,” says Nicholls. “Even then, having made the tape he didn’t want it to become public until well after his death.”